These are difficult times for the Karen of Ler Doh Soe Township in Burma’s Tenasserim Division. Just a decade ago, the Karen National Union (KNU) held sway over the area. In those days Karen could be Karen. Every village could boast of having a primary school, food was abundant, and Karen cultural life was flourishing. Traders, farmers, and housewives could be seen attending to their responsibilities in strings of sleepy villages that seemed to have escaped the meddling hand of time. The lush jungles, rugged hills, and slow moving brown rivers made the abusive and inept governments in Rangoon seem light-years away. For generations, Karen born in the region experienced peace and prosperity, but that was before the Yadana pipeline project and the 1997 Burmese Army offensive.

For decades, military dictatorships in Rangoon paid little attention to the remote portions of Tenasserim division. But in the early 1990's events changed radically: the Burmese Army, condemned internationally for human rights abuses, began pouring into the area. Whether they came in conquest or, as many have speculated, because they realized the economic potential of the area, the outcome was still the same: the fracturing of tens of thousands of Karen lives.

“I know in my heart, if we say we stand for human rights - then we must stand up all the way.” Padoh KB

Today, Padoh KB, a Karen National Union (KNU) official in the region, has to shoulder an immense administrative and emotional burden - one that at times seems almost overwhelming. Since the 1997 Burmese Army offensive, this once tranquil region is now a land of burned villages, land mines, free fire zones, malnutrition, rape, forced labor, and concentration camps. Yet the Karen here languish in the same manner that they formally prospered, in silence and obscurity. But leaders like KB will not allow the savagery and misery of their environment or the seeming indifference of the international community to blunt their compassion, reason, and vision for the Karen people.

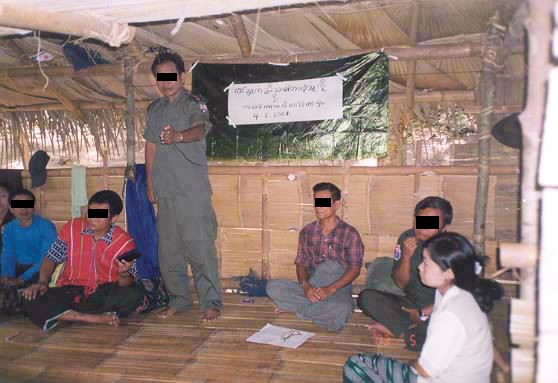

In a simple bamboo hut located in dense jungle, a gathering is being held. Assembled are villagers, soldiers, IDPs (internally displaced persons), as well as escapees from concentration camps. As the people excitedly prepare food for the meeting, a small piece of paper hanging on the wall of hut announces the nature of the assembly: a ceremony and celebration. But what is there to celebrate? The people gathered around are impoverished; they have no country; many have lost their homes, livelihoods, and loved ones; Burmese troops surround the area. The celebration is for a group of boy soldiers and other IDP children who will begin new lives as students.

“In our current situation many boys unavoidably came and joined our troops. This is due to the oppression and abuses that we face from the Burmese military dictatorship. We did not want to allow them to become soldiers, so we have been searching for ways to send them to school – and we now have an opportunity. In this ceremony, I would like to show that boy soldiers are no longer accepted in the KNLA.” Major LH, KNLA (Karen National Liberation Army), Boy Soldier to Student Ceremony, May 2003

Boy soldiers in Karenland: A complex and emotional situation

In 2002, the nation of Burma achieved the ignominious distinction among the international community for its unprecedented use of boy soldiers. A report by Human Rights Watch detailed the use of boy soldiers not only by the Burmese military dictatorship (SPDC), but also by the resistance forces, including the KNU.

I have interviewed boy soldiers that have been fielded by both the SPDC and the KNU. Based on my experience, KNLA (Karen National Liberation Army – the military wing of the KNU) boy soldiers are volunteers, unlike their Burmese Army counterparts, who are often kidnapped and pressed into military service. KNLA boy soldiers are also not subject to the physical and verbal abuse that SPDC boy soldiers must endure in training and from their NCOs (noncommissioned officers). Most of the Karen boy soldiers that I have encountered were orphaned, whose parents and other family members died directly or indirectly due to Burmese military operations. Although this does not free the KNU from culpability in this matter, it does shed light on a complex and emotional situation.

The Karen are fighting not a war of conquest, but of survival. One Karen boy soldier I witnessed was the 14 year old bodyguard of a KNLA colonel. The boy had taken flight from the Yadana gas pipeline area where his mother and father had both been killed by the SPDC. Enraged and isolated, the boy joined the KNLA. Unfortunately, this type of scenario is commonplace in Karenland, and found full expression in the formation of the youthful God’s Army movement. As one Karen officer in the region commented on the phenomenon of boy soldiers in the KNLA:

“They come to us with nothing - no food, no mother, no father. Their villages have been burned. They want to fight. They hate the Burmese army. If I tell them go home – well, they have no home.”

“The situation is very hard for us. Even our children have to struggle to survive in the jungle like they are adults.” Padoh KB

After the 1997 offensive, thousands of Karen fled to the Thai border. Some groups were granted sanctuary by the Thai government and were moved to refugee camps. Others, including women and children, were forced back into war zones by the Thai Army and subsequently became IDPs. Thousands of Karen in Tenasserim Division found themselves in SPDC administered concentration camps and consolidated villages where they were viewed as a conquered and servile people. Other Karen, estimated at six thousand, sought sanctuary in the jungles where life proved to be miserable. Many of the Karen who found refuge in Thailand fared little better, for initially they were forced to sleep on the ground during rainy season. “Many of us died of illness that first year,” recounted one refugee. Conditions had improved only marginally when the High Commissioner of the UNHCR toured Tham Hin refugee camp in 2000. High Commissioner Sagato stated that the conditions in Tham Hin were “shocking.”

For those Karen hiding in the jungle, life boiled down to one simple fact: survival. Within this environment of danger, deprivation, and uncertainty, some boys, many of them orphans, attached themselves to KNLA units. The boys were not welcomed, but they were not turned away either. Unlike the God’s Army, boy soldiers in the KNLA were kept away from the front line and were used primarily as camp stewards.

Boy soldiers in the God’s Army: a response to a human catastrophe

Karen from Tenasserim Division reflect mournfully on the God’s Army movement. As one Karen refugee stated:

“They were not political. They were ignorant of such things. They only wanted to fight the Burmese Army who had made their lives hell.”

The reckless operations of the God’s Army, which was allegedly led by mystically-inspired Karen teenage twins, proved to be a propaganda coup for the perpetually embarrassed SPDC, a tasty tidbit for the international news media, and an excuse for the Thai government to further estrange its former Karen ally. Unfortunately, the real factor underlying the God’s Army movement was all but ignored by all the parties mentioned above. The movement was a desperate response to the Karen human catastrophe in Tenasserim Division. The bold and rash operations conducted by the God’s Army, both in Thailand and Burma, exemplified this sense of hopelessness and desperation. While thousands of Karen were enduring unspeakable abuses at the hands of the Burmese Army, the news media tended to focus on the eccentricities of the God’s Army, including its use of boy soldiers. The comic book portrayals of a backward ethnic cult composed of boys grasped the international consciousness briefly. As the God’s Army met its swift and brutal demise, the horror for the Karen in Tenasserim persisted.

Boy Soldier to Student Ceremony May 2003

“We are going to send our children to school as we did in the past.” Padoh KB

Despite the fact that the villagers in his area are living along the margins of survival, the site of boys in uniform has always been disturbing to KB. A few months ago, a friend of the Karen approached KB about the matter and offered support and encouragement. A plan was formulated and the necessary arrangements were made. Twelve boy soldiers (ages 10 to 16) as well as seven IDP girls (ages 9 to 14) would trek to a safe area and begin a new life as students.

“In this ceremony we would like to show that child soldiers are no longer accepted in the KNLA.” Padoh KB

What occurred at this ceremony can never be trampled upon by the Burmese dictatorship. It is out of the reach of their powerful weaponry. They will never subdue or compel it. It is the power of humanity to reason and show compassion even in the direst straits and the darkest jungles. Good luck to the new students!

“They belong to the school, not the military.” Captain ST hangs a school bag on the shoulder of a former boy soldier.

The Ceremony.